By Theresa Kulbaga

She was a 1970s folk-pop artist with long hair draped over her sweater. She had a one-of-a-kind voice, tinged with a charming, breathy lilt and a preference for underused vocables. She made poetry out of lyrics and guitar and piano. She liked the word “grim.” She is a favorite of Carrie Brownstein and many others—in fact, she had a major influence on the mainstream songwriting of the 1970s and beyond. Her first name begins with a swooping J.

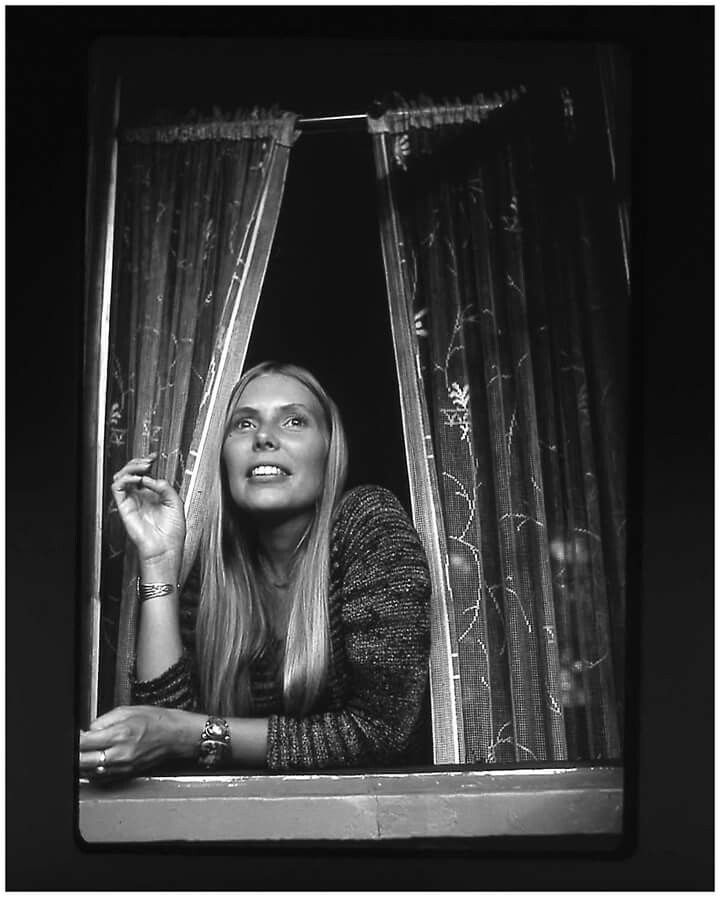

No, I’m not thinking of Joni Mitchell.

Instead, I’m describing forgotten folk genius Judee Sill. Sill had glasses and a sharp, intelligent face. She was classically trained, a great fan of Bach. Her favorite philosopher was Pythagorus. She was bisexual. She sang and spoke with a twang, loppin’ off the Gs at the ends of words like “lopping,” and sayin’ “real little kid” instead of “really little kid.” She was deeply religious, even mystical in some of her lyrics and themes. But she also robbed liquor stores and gas stations, earning a criminal record (“I learned a lot of good music while I was in The Joint,” she told Rolling Stone), and she died at 35 of an overdose after years of heroin addiction and halfhearted sex work.

Sill released just two albums in her short career: Judee Sill (1971), with its unforgettable single, “Jesus Was a Cross-Maker,” produced by Graham Nash, and Heart Food (1973), which was written, arranged, and produced solely by Sill herself. In these albums, what you’ll find is the keen and earnest wisdom of a woman who was wracked and haunted her whole life but who somehow remained witty and untinged by cynicism.

While Judee Sill draws regular comparisons to Joni Mitchell, Carole King, and other folk artists of the 70s, listening to her songs is its own experience. At times, she strums the guitar and sings sadly of heartbreak and despair. Other times, she weaves a chorus of voices and piano and organ into a Baroque composition, singing

Kyrie eleison, kyrie eleison

So sad, and so true

That even shadows come

And hum the requiem.

Other times, she sings—weirdly—about visions and supernatural things, as in the live recording of “Enchanted Sky Machines,” which she prefaces with a religious interpretation: “It’s about flyin’ saucers at the end of the world comin’ to take the people away from their sufferin’. It’s a rapture. And it’s a religious song.”

She is both funny and dead serious, devoutly sexy and self-aware and unabashedly Christian. “I try to keep my hungry monsters in line – keep ’em on a diet of bread and water,” she said in an interview. And in “The Phoenix,” she sings

The sun was red, and the fires were roarin’

Stars aligned and the webs were spun

I coulda sworn I heard my spirit soarin’

Guess I’m always chasin’ the sun

Hopin’ we will soon be one

Until it turns around to me, then I try to run.

Sill termed her sound “country-cult-baroque.” But it also has elements of folk, pop, rock, classical, gospel, and blues. Her most famous song, “Jesus Was a Cross Maker,” gained new popularity in 2018 when Asia Argento posted photos and videos of the song to her Instagram stories five days after her ex-boyfriend, Anthony Bourdain, took his life. (“Blindin’ me, his song remains remindin’ me / He’s a bandit and a heart breaker / Oh, but Jesus was a cross maker.”) On her live album, she says of this song, which she wrote about a bad relationship, “I realized that bandit bastard [her ex] was not beyond redemption. It’s true, I swear. It saved me, this song. It was writing this song or suicide.”

But she sings as much about crime, and about livin’ on the streets, as she does about God. In “Dead Time Bummer Blues,” a bluesy romp about marijuana legalization, she wonders from a jail cell, “what the fuck am I doin’ here?” (“I’m doin’ all this dead time / For the partaking of a plant / The earth says ‘help yourself’ / But the law maintains I can’t.”) And in “The Pearl,” she sings “I’ve been lookin’ for someone who sells truth by the pound. / Then I saw the dealer and his friend arrive, but their gifts looked grim.”

My personal favorite Judee Sill track combines these disparate musical influences—Bach, blues, gospel, folk—with Sill’s profound and humorous lyrical worldview. In “Lopin’ Along Thru the Cosmos,” Sill combines a gentle acoustic guitar with swelling strings and orchestral horns. She sings the lyrics with especially hard Rs and especially lopped Gs. The song is about—depending on your perspective—either human or divine relationship, about learnin’ not to hope too hard for a certain outcome. Just let it be, Sill suggests, and everything will be fine:

lopin’ along through the cosmos

and sideways I slide through the square

I’m hopin’ so hard for a kiss from God

I missed the sweet love of the air.

so keep on movin’

or stay by my side, either way,

I’ll tell you a secret

I’ve never revealed:

however we are is o.k.

Or perhaps the song is about Sill’s relationship with the music industry. She described the music business as “real sick,” and her relationships with industry insiders were fraught. Her albums were not commercially successful. When she died, she had stopped making music, and she lived in a mobile home, re-addicted to heroin and in pain from chronic back injuries.

Maybe—hopefully—she still heard the music of God from time to time.