Marissa Paternoster, the powerhouse frontwoman of New-Jersey-Based band Screaming Females, thinks in line and shape as much as in music and lyric. Her eerie, intricate pen and ink drawings, which she sells at Forgotten Grin, are simultaneously abstract and palpable, full of anxiety and pain and writhing bodies—but wry humor, too.

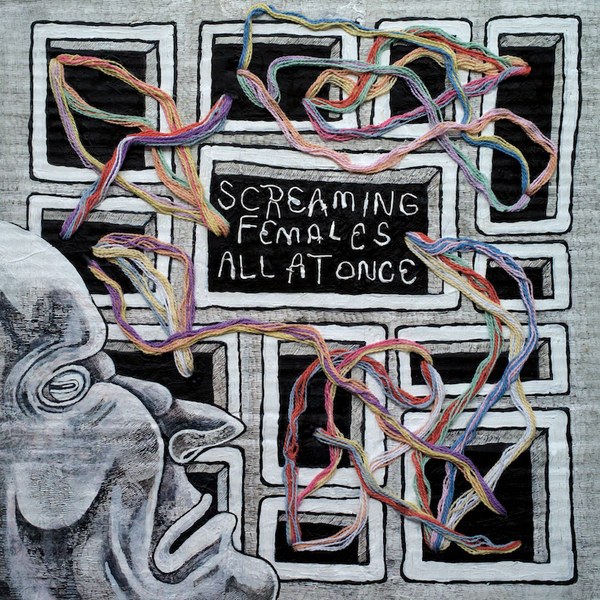

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that Screaming Females’ new album, All At Once (2018)—the band’s most pop-punk and thoroughly listenable work to date—is full of references to the visual arts and to other artists. I’m always interested in Screaming Females’ lyrics, which offer a kind of esoteric poetry that seems interestingly at odds with their killer riffs and hooks. All At Once is largely about the importance of art; the lyrics evoke color and line and material in a way that had me Googling artists and pondering the risks and rewards of painting and being painted, seeing and being seen.

In “Glass House,” the album’s opening track, Paternoster sings about “painting myself in all four corners” of a glass house. The song describes being boxed in and controlled—by fame? misunderstanding?—and the desperation that results from feeling constantly exposed in that way. As the crescendo builds to the final chorus, guitar and drum echo Paternoster’s voice in panic: “my life in this glass house / impossible to get out.”

“Agnes Martin” is a tribute to the American abstract artist, who created serene paintings composed of grids and lines and stripes. These lyrics suggest obscurity rather than exposure: “tonal oblivion / no rooms in this desert made of light.” Martin’s work was both spare and radical: by using the subtlest of colors and variations, she made her boldest mark. In “I Love the Whole World” (1999) for example, she painted a five-foot-square white canvas with the palest of peach stripes. They are barely noticeable. In “Petal” (1964), she lightly traced a subtle grid on brown paper with a ruler. Even her brighter works play with monotone; in “Starlight” (1963), she suffused a dark grid with an equally dark blue watercolor wash. “She’s unseen completely,” Paternoster sings—whether longingly or sorrowfully, it’s hard to tell. “The sun destroys me.” She is ink on paper, delicate but colossal.

Agnes Martin. I Love the Whole World. 1999. Acrylic on canvas.

Photo credit: Tate.

In other songs, painting is precisely not subtle enough. “You draw me in disguise / And paint me paralyzed, it’s true / You trace me as you see / The darkest color, deepest blue.” These lines, from the track “My Body,” lament the pain of being misrepresented and misunderstood by another. No subtle peach hues here, no delicacy in the sun; instead, we see her traced wrongly in “darkest color, deepest blue.” But the misunderstanding apparently cuts two ways: “I tried to draw you too / But in bad taste and with poor choice / And I can’t paint like you do / Tragic precision, perfect void.” Because of the band’s last album, Rose Mountain, and its songs about Paternoster’s difficult relationship to her body, I wondered if “My Body” couldn’t also be about that other misunderstanding, not interpersonal but intrapersonal, internal, private.

My favorite art reference on All At Once is “Bird in Space.” This ultra-melodic song imagines the speaker cast in bronze, as in Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși’s 1928 beauty, Bird in Space. The song opens with the lines, “I flirt with Brâncuși’s gesture / I’m a bird in space,” which is how I knew to look it up. I was smitten: this abstract, minimalist sculpture captures a bird in mid-flight as a single, curved line. It is breathtaking. In Screaming Females’ song, the chorus captures the desire to be like the bird in space, hard, beautiful, bodiless: “I’ll look nice like a bird in paradise / Forever caught in mid-flight.” The opposite of a life in a glass house? Possibly.

Constantin Brâncuși. Bird in Space. 1928. Bronze.

Photo credit: MOMA

Not every song on All At Once has such an intellectual bent. I especially love “I’ll Make You Sorry,” with its upbeat, head-bopping pop sound and its resigned shrug of a message: “I once was in love before I knew you / but I’ve given up. / I once was in love before you / I’ll make you sorry!” There’s “Soft Domination,” featuring a guest appearance by Fugazi’s Brendan Canty. And the final song on the album, “Step Outside,” is a feminist anthem about street harassment and violence: “I’m sick with worry just knowing / when you step outside you won’t be safe.”

Marissa Paternoster. You’re Mean. 2017. Pen and ink on paper.

Photo credit: Forgotten Grin.

But I like the songs that invite me to learn about art, too. They feel like a peek into the glass house of Paternoster’s artistic mind, full of wild music and poetry and wonderful sketches. I wonder if Agnes Martin and Constantin Brâncuși are favorites, if they inspire Paternoster’s own pictures. They seem so different—but then Martin works in pen and ink on paper, like Paternoster, and Brâncuși’s sculpture is both abstruse and accessible, just like Screamales’ new album.

Agnes Martin. Starlight. 1963. Watercolor and ink on paper.

Photo credit: Guggenheim.